‘We’ll leave the title ‘till the end,’ said Clare, looking a bit doubtful.

I – as the literal translator – had translated ‘Mots ris, tant niés!’ as ‘Words laughed, so denied!’. When I asked poet Mamoudou Lamine Kane what this title meant, he pointed out – rather sheepishly, to be fair – that it was a play on the name of his country: ‘Mau-ri-tanie’. How on earth were we going to do that justice, the group of translators at the poetry Translation Centre wondered.

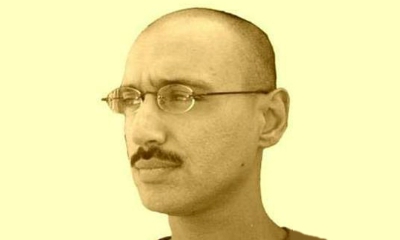

I came across Mamoudou Lamine Kane in Paris’s Présence Africaine bookshop. On a rainy February morning, I’d perched on a book-filled carboard box to flick through the shop’s poetry collections. Présence Africaine is not a cutting-edge bookshop or publishing house; rather, it pays respectful tribute to the great names of francophone African twentieth-century writing. But I found myself drawn to this relatively young poet, whose first collection – the only one stocked here – was published in 2009. I discovered that he is also an economist and blogger. Ok, I thought, tell me more.

I was struck by the themes of Mamoudou’s poetry. ‘Taxidermist houris’ wander among squealing mullahs and obese apostles – figures representing the major world religions whom the poet berates one by one – while a ‘tormented yellow eye, still half asleep / Peers over the zinc rooves’. I was drawn to the shock of the words, cushioned in a simple form, with comforting rhymes here and there, and repeated words, inviting familiarity.

I tried two methods of contacting Mamoudou to obtain his permission for translation. The first, through his publisher, went in vain. The second – a Twitter request for his email address – prompted an almost immediate response. From this point, Mamoudou and I entered into a correspondence, and I was glad to have this chance to learn about Mauritania: a clash of cultures and contemporalities, I discovered. Above all, he was great at answering my questions – without his input, we may’ve been left translating the title as something to do with laughing words and denial.

In the workshop, Clare Pollard walked the group of translators through the poem she’d chosen for us to translate. It begins at a gridlocked intersection of Mauritania’s capital, Nouakchott, during morning rush hour. Opening up each term to discussion meant that images I’d assumed the authority of for months were suddenly in question. I’d thought the intersections (or crossroads) were ‘rougis’ – reddened – from the traffic lights overhead; but it suddenly seemed obvious that the red was the clay of the roads.

Almost every term was discussed. Could arrogance be plural? Were the arrogances pouring out and along the pot-holed roads, or down onto them? And were the people on their way to hazy, vaporous, obscure, flimsy, mysterious, or vague occupations? (And is it paradoxical to try to pinpoint such a concept?)

The most debate arose around two descriptions. The first:

Tant de foi greffée sur la moelle de la cupidité (So much faith grafted to the marrow of greed)

Immediately invited caution from Clare, who pointed out that you can’t really graft something to marrow, since marrow is what you find inside bone. After much discussion, we returned to something not a million miles from the literal, but which replaces ‘grafted’ with ‘bound’.

The final stanza: ‘Les pensées noircissent,’ (thoughts blacken) ‘chauffées à blanc’ (heated until white hot); But then: ‘Lorsque pour les éclaircir’ (‘When, to clear them up,’ I’d suggested – but why would you clear up/make clearer/lighten white hot thoughts turned black?). We performed the biggest reconstruction work on this section, arriving in the end at:

Blackened thoughts are heated white hot./ Return to solitude for clarity/ But find the shadow cast there too.

It was time to tackle the title. This came, in the end, much more easily than I expected.

‘We have to use a pun,’ stated Clare.

I wondered if we could go with ‘More-itania’: it was a play on the country name that hinted at the desire for material gain. But this wasn’t enough.

‘More… Itania?’ Someone pointed out, emphasising that ‘itania’ didn’t mean anything.

‘More rich taints yer,’ came one suggestion. We liked it. What did it mean? Well … here we were sketchier. But did we have as much conviction as Mamoudou Lamine Kane regarding ‘Mots ris, tant niés’? Yes, we probably did.

Clare stepped back to read our sheets of scrawled translation. She read as confidently as if performing verse she’d spent hours rehearsing. She made our work sound like something well put together, when in fact we’d been concentrating on each line in such close detail, there hadn’t been time to contemplate the whole until now. And yet there it hung before us: a poem rising from the dustbowl gridlock of the morning commute, floating above the rooves of the ‘capital’s island of riches’ to land ‘in the privacy of dusk’, burnt to a crisp. It was either Clare’s genius in session guidance at work, or her expert delivery. I couldn’t tell which.