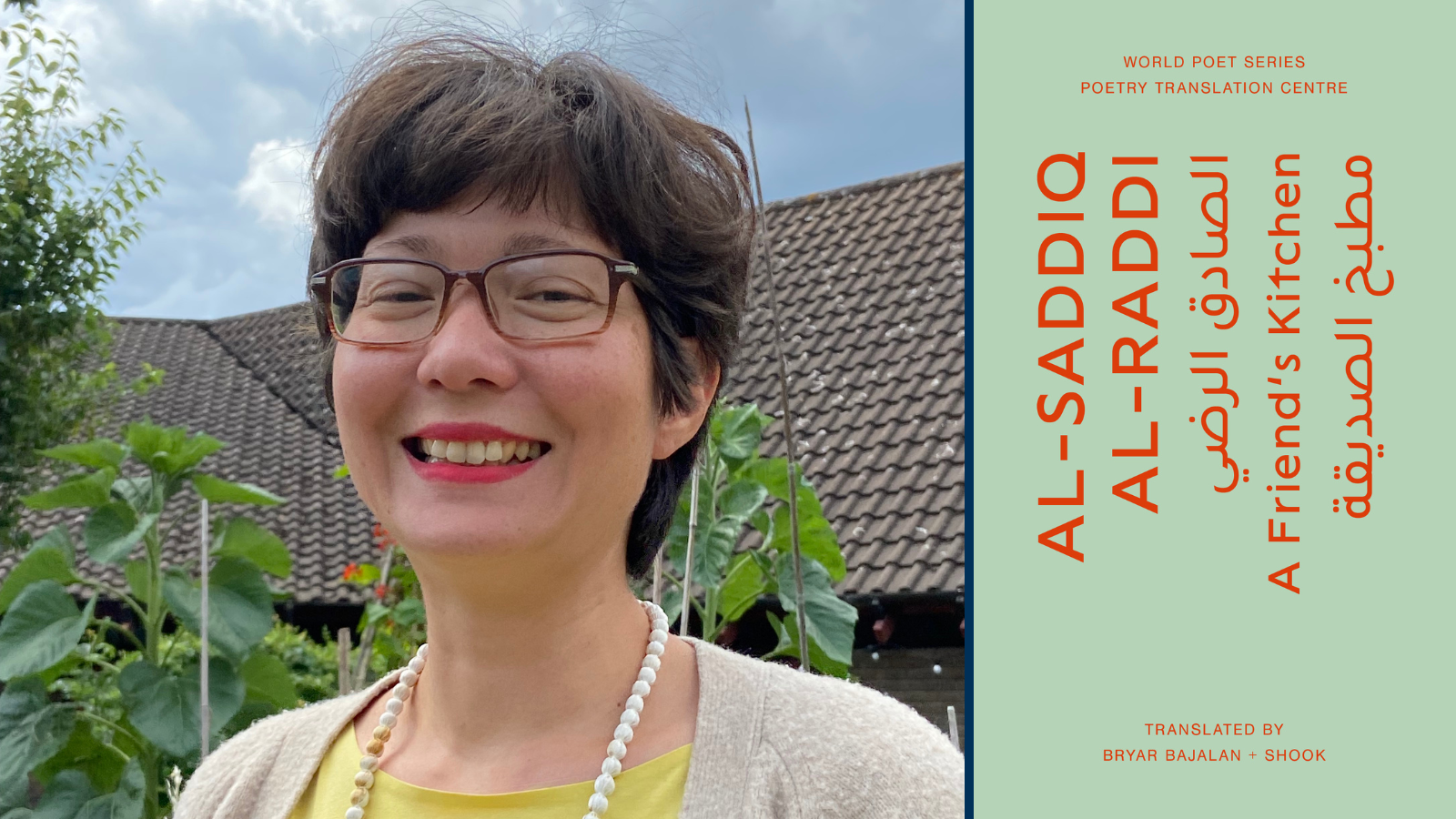

PTC Director Erica Hesketh reflects on the process of editing A Friend’s Kitchen.

I’ve always thought that poets and translators have an important thing in common: they both work with language at extremely close range, attending to its music, metric and meaning—the materiality of it—with the expert attention of piano tuners, ears held close. Both poets and translators balance sense and music, access and strangeness, context and individuality, to achieve their desired effects through words.

As an editor of translated poetry, one of my jobs is to enter this attentive space together with a poem’s translator(s), to tap on word choices and line breaks to test their resonance, and to help a poem become its best self in the target language. I have to say there is nothing I love more than an editorial session for a translated book of poems; the discussions that flow from specific questions about vocabulary or register are always fascinating, educational (for me) and invigorating (for all of us I hope).

In the case of Al-Saddiq Al-Raddi’s A Friend’s Kitchen, I had several meetings via Zoom with Al-Saddiq’s translators, Bryar Bajalan and Shook, who worked together in a collaborative way to produce the translations, with frequent calls to Al-Saddiq for clarification. Bryar is a translator, poet, film-maker and researcher originally from Iraq, while Shook is an accomplished American poet who has been friends with Al-Saddiq for nearly two decades and knows his work well. Every collaborative partnership functions differently, but something I really appreciated about Bryar and Shook’s partnership was their mutual respect, the clear sense of what they each brought to the project as artists. The three of us met for sessions of a few hours at a time, working slowly through the translated text and stopping at unresolved or knotty lines to discuss them in depth.

Al-Saddiq’s poetry is intimate and personal, and in a way quite emotionally direct. But it is also full of Quranic references and language, which has both Sufi and political echoes and sub-echoes – not straightforward to convey in English, at least in as many words! One example we scratched our heads over was the opening of ‘Panic Attack’, where the speaker is addressing a beloved about the Day of Resurrection, which according to the Islamic belief system is the day when all humans are held to account for their actions in life and called to heaven or hell.

The poem begins with the line: ‘Yes, on Resurrection Day we will spend from our secret account.’ The second line in Arabic translates directly as something like ‘It is never reasonable, to forget this way,’ which we spent a while unpacking. We learned that it relates to the idea that every human approaches Judgement on their own behalf, leaving behind (‘forgetting’) everyone they have known in life. In essence this opening couplet presents the radical and potentially dangerous idea that the speaker and their beloved might remain connected somehow—and the poem goes on to describe intimate moments that the speaker could never forget, e.g. the beloved’s flirtatious laugh, the sound of the phone ringing, etc. To make this whole idea clearer for the English-language reader, we settled on ‘How could I think only of myself? Impossible’. It didn’t capture everything from the original Arabic (and its background assumptions), but it felt true to the emotion of the line, and gave it a subject in the form of the ‘I’, which took us nicely into the next section which is more image-based.

As always when it comes to translation, some things had to be left behind in the Arabic (but not forgotten!). World Poet Series books always display both languages side-by-side, so hopefully readers can explore further for themselves. Bilingual readers may want to have a go at their own versions! I am a firm believer that translation is a contingent activity that will happen differently for different people, at different times, in different contexts, etc. Bryar has also written an excellent introduction to the poems which sheds light on Al-Saddiq’s use of language, and where he is coming from as a poet. I really hope readers enjoy the poems in this collection, and come away with some sense of the process of conveying—or remaking—poetry between languages.

Erica Hesketh is the Director of the Poetry Translation Centre.