Published in The Guardian, Saturday October 15 2005

Kevin Rushby joins poets from Sudan, Afghanistan and Somaliland on a tour of the UK and discovers that years of repression and exile have left scars but also nourished strong literary traditions

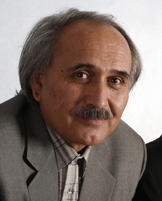

It’s an unusual accolade for a poet a death threat: Maxamed Xaashi Dhamac “Gaarriye” got his in 1980 and it came via the Somalian president Siad Barre. “He even said anyone caught selling a particular poem [of mine] on audio cassettes would be executed Gaarriye recalls.

The power of verse to cause social upheaval is not something we’re very familiar with in the UK, but in Somali culture it’s taken for granted. One poet starts a theme, others take it up, then a chain develops, drawing people into the arguments. I wrote something against tribalism that became an attack on the president Gaarriye explains. Within four months the chain was more than 70 poems long.” And that was when the secret police came to visit. Shortly afterwards he fled to Ethiopia and an exile that lasted until 1991.

Gaarriye is currently touring Britain with five other poets. Each is expected to find an audience among the communities of migrants from their home countries who have settled here – communities that have often been ignored or vilified. In three cases – Somaliland Sudan and Aghanistan – they are countries that have seen recent or ongoing conflicts. These are also places where poetry has a particularly important role.

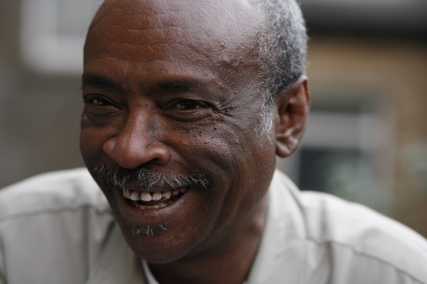

Al-Saddiq Al-Raddi a 35-year-old Sudanese writer lives in Khartoum and is already a veteran of many years of artistic repression – one of his hands bears the scars of a vicious prison beating. Partaw Naderi an Afghan poet who writes in Dari spent time in the notorious Pul-e-Chakhri prison in Kabul then five years in exile. The poetry these writers produced during such periods of hardship reflects experiences shared by many of their compatriots now living in the UK:

“I come from a distant land

with a foreign knapsack on my back

with a silenced song on my lips.”

(from “My Voice” by Partaw translated by Sarah Maguire and Yama Yari).

For Al-Saddiq years of enforced silence when he was barred from public readings left him with a feeling that each poem might be his last.

“I had somehow to hide

the frail blood-stained shoots of April

inside me; I had to allow the crimson night-sky

its majesty; I had

to learn how to stain

the space of the present

with what seeps from a forgotten wound.”

(from “Weaving a World” translated by Mark Ford and Hafiz Kheir).

For Gaarriye the years when he was spied on and monitored were suffocating but poetically his most productive. “I can’t escape that experience he says. And it’s a shared experience – that’s why the community listen to me.” In 1978 he wrote a poem to mark Nelson Mandela’s 60th birthday which coincided with the release from prison of his friend the poet Hadraawi after five years’ solitary confinement:

“This poem is a gun.

This poem’s an assassin.

Images mob my mind …

This pen’s a spear a knife

A branding-iron an arrow

Tipped with righteous anger.

It writes with blood and bile.

(from “Mandela” translated by David Harsent Martin Orwin and Maxamed Xassan “Alto”).

In Afghanistan as in Somalia poetry has played a decisive role in recent history. “The mujahideen sang poems going into battle Partaw says. The communist government tried it too. Then when the Taliban arrived in Kabul they were reciting poetry.” He stayed for a year under Taliban rule watching as they closed down publications and locked up artists and writers. Finally he fled to Pakistan where he found others who were expressing themselves in verse drawing on traditions that reach back to the 13th century and the Sufi mystic Jalal al-Din Rumi – himself a refugee who fled his home in northern Afghanistan ahead of the Mongol invasion. “We say poems are part of our mother’s milk Partaw says, and that all of our culture came through poetry.”

English readers have long had access to Persian poems with 19th-century translations of Omar Khayyam Hafez and Rumi – a recent translation of the latter was a bestseller in the US. But the lack of a written Somali tradition has closed it off from outsiders. The language did not have an official script until 1972 and even now there are no adequate dictionaries for literary translation.

Martin Orwin a lecturer at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London and the only British academic fluent in Somali points out that this creates an enormous barrier to study. “If you can’t speak Somali it’s impossible to study the poetry – you have to learn the language and that’s difficult without the right tools.”

Isolated though it may be the Somali community in Britain has found in poetry a source of strength. Abdulghani Sabban who works as a community support teacher in London points out that recitals are common “especially during qat sessions” – a reference to the mild stimulant leaf much liked by Somalis. But some young Somalis have little or no idea about their own heritage. “With one group I had to use English translations of Somali poetry Abdulghani says. Only then did they began to grasp the implications of it.”

Gaarriye’s role in the famous chain poems has made him something of a legend among the Somali diaspora – on his second day in the UK his phone is ringing constantly with invitations to lunch or more often chew qat (“I write all my poems while chewing it he grins). His fame clearly delights him, but he’s aware that it rests on an historical accident. In the mid-70s just when he began writing poems, tape-players arrived in Somalia. Students started copying my poetry on to cassettes. That idea really spread like wildfire. We’re a nomadic oral society in which poetry is the most important art form – cassettes were perfect for us.”

The use of cassettes maintained poetry’s central role in Somali society – and also kept refugee communities in touch with latest developments – but it was when Gaarriye came to write down the rules of poetic metre that the art form’s future was truly secured. He now teaches Somali literature at Hargeisa university in Somaliland and translations of Somali verse are beginning to introduce new readers to this previously hidden tradition.

Sarah Maguire founder and director of the Poetry Translation Centre believes that British poetry can benefit hugely from the infusion of foreign influences. “Think of how modern European poetry was effected by Ezra Pound’s work on Chinese poems or how my own generation were deeply influenced by translations of east Europeans like Akhmatova she says.

Gaarriye, the man whose very public poetry helped shape his country’s history, is in full agreement. Somali poetry is already changing, he says; the memory of days when revolution was kicked into life by chain poems is fading, to be replaced by more peaceful concerns. We’re starting to develop an aesthetic side he grins, as he slides out to an engagement with another Somali social group and, no doubt, a few leaves of qat to tickle the muse.

· Maxamed Xaashi Dhamac Gaarriye” Al-Saddiq Al-Raddi and Partaw Naderi are touring the UK for the Poetry Translation Centre’s World Poets’ Tour with events at Ilkley Playhouse tonight at Glanfa Millennium Centre Cardiff on Wednesday; and at the Scottish Poetry Library on October 26.