I once summed up my own poetics in three sentences:

- I must write every poem as the very last piece

- I must give all your energy to every line

- I must fight to break through with every word.

For a poet, writing is like running a marathon, but that’s still not enough, as my marathons must be run from start to finish at the speed of a 100m sprint. Every step is the ‘last poem’: it pursues me like a precipice, so there is nowhere to turn back to, and I can only go forward. Every word I write is starting from the impossible.

Who should be rejoicing at Anniversary Snow winning the Sarah Maguire Prize? Me? Or the Li Bais and Du Fus hidden in this collection of poems, that three thousand unbroken years of the Chinese poetic tradition? The historic melancholy laid down like sedimentary rock inside the Chinese characters, the beauty of language as striking and strange as bronze, and as elegant as Song Dynasty porcelain, has been waiting too long. The reincarnation that contains so many dead souls has happened too many times. The loneliness of the Chinese language is an unbreakable destiny.

I’ve forgotten who said that the biggest language in the word is translation. I think we should add another sentence: the deepest language in the word is also translation. In particular, poetry translation is where two cultures open their inmost hearts to each other, making possible an encounter between lifeblood and soul. In a translated poem people read a self materialising out of another time and space, and are moved or stunned, but never in the least surprised by the magic trick of distance. It seems to be the original nature of poetry: no matter whether it happens far away or close by, if hits the heart, it is always here and now.

The numbers increased by globalisation, if they are not integrated into our spiritual values, are nothing more than making humanity’s bubble.

The forty years I have been writing have coincided with the modern transformation of China’s ancient cultural traditions. The tribulations of the Cultural Revolution were my starting point, the historical and cultural introspection of the 1980s augmented my mental energies, my international wanderings since the 1990s opened my eyes to the human predicament, and the universal spiritual crisis of the 21st century, moving from chaos to vacuum, brought with it a despairing insight: have we never left our conceptual concentric circle? The only image of a poet is that of a questioner, the only position for poetry is that of a survivor. It’s easy to call yourself avant-garde, but what is difficult is to become the arrière-garde, that delayed effect, that resilience, which preserves and maintains thoughtful poetry. Every poem in Anniversary Snow is rooted. A rich blood relationship connects real life to real language. Within the relative depth of various different topics, the poetic mode of thinking has never changed, ancient or modern, in China or outside it, for they are our common grammar. Anniversary Snow drifted down onto a map of the mind – political, historical, cultural, linguistic – and solidified into the pangs of conscience and the beauty of creation. We meet here.

My 25-year collaboration with Brian Holton is, you may say, a heaven-sent affinity. Through thirteen books, up to Anniversary Snow, we have been the founders of our own little tradition, which is a unique phenomenon in contemporary Chinese poetry translation. Brian’s poetic gifts, his knowledge of Classical Chinese poetry, and his beautiful Scottish musicality all meet what my poetry demands: conceptual innovation, formal precision, experimental language open to all directions – including the invention of prosody in order to transform the spirit of classical poetry – our quarter-century of translating has encompassed three thousand years of the Chinese language, and we are still creating more of it! By looking at it through a translator’s eyes, my poetry has been examined anew, whether or not it qualifies as what I wish, to be ‘Chinese poetry of global significance’.

Anniversary Snow has won the Sarah Maguire Prize, like a happy conjunction of time and space, between the Chinese language, which continues its three thousand years of creative transformation, and English, the language with the widest global coverage, for in poetry each mutates into the profundity of the other. The poet-translators in this book who have no Chinese are the finest example of this deep exchange. With me they carved away at making a target text, word by word, line by line, poem by poem, based on the realisation of the aesthetic demands of the original piece, to grow a different tree on the same root, thus pushing to its extreme the maxim that poetry can’t be translated – poetry can’t not be translated – the more difficult the poetry, the more it’s worth translating. The collaborative anthology we produced has the title The Third Shore, after Walter Benjamin’s wonderful statement, ‘translation is a third language’[1] . The waves of the ocean of globalisation are breaking on the third shore everywhere and perhaps we even only have a third shore?

In conclusion, I’d like to use the final line of A Sunflower Seed’s Lines of Negation, which Bill Herbert and I polished together:

refusing to let the poem sink into dead indifferent beauty [2]

As long as this little candle of poetry is not snuffed-out and cold the great darkness of History will never be able to overwhelm human nature.

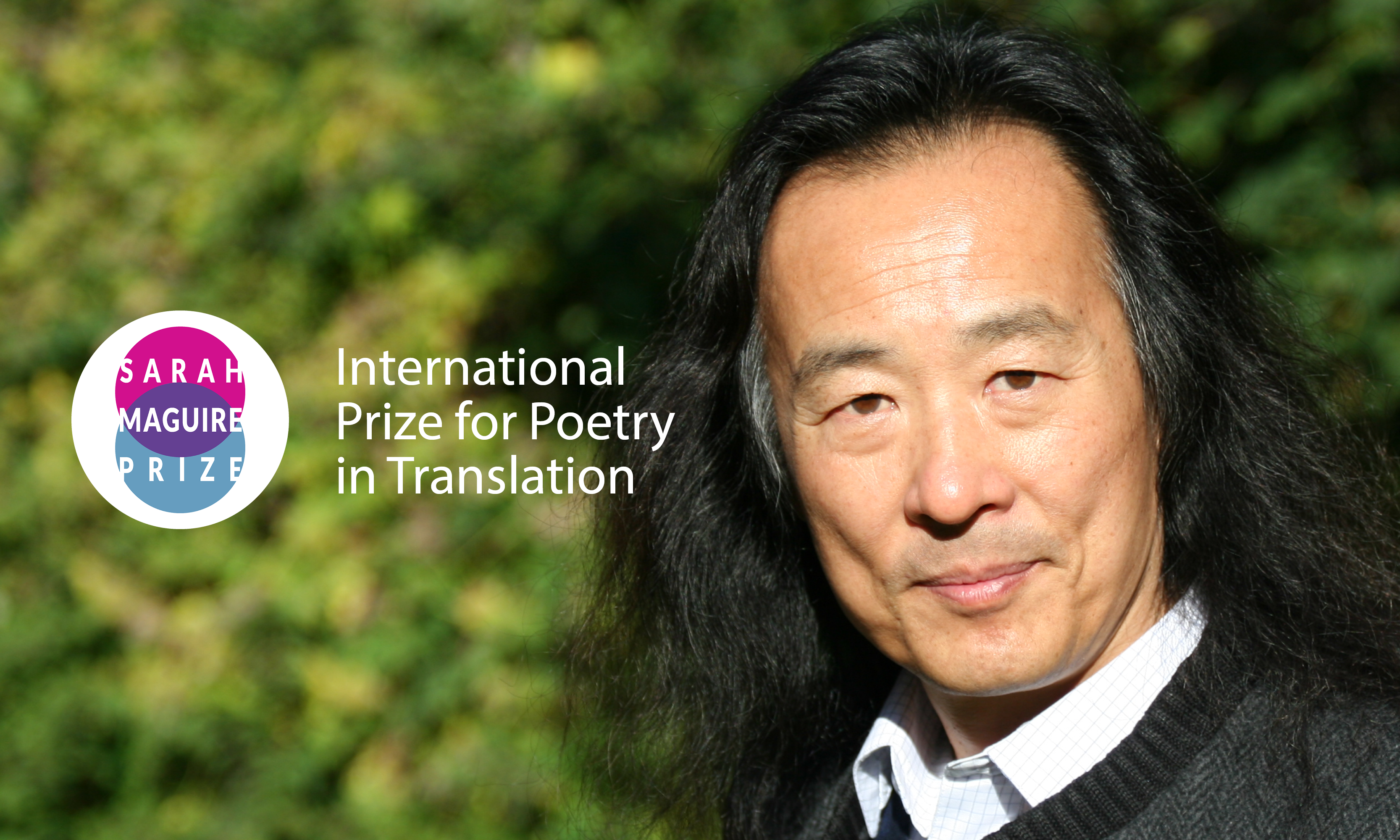

Yang Lian

Berlin

19th March 2021

______________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Eds. Herbert, WN, Yang, Lian Shearsman Books 2013

[2] Translator’s footnote: Brian Holton worked on this poem, too.

Translated by Brian Holton