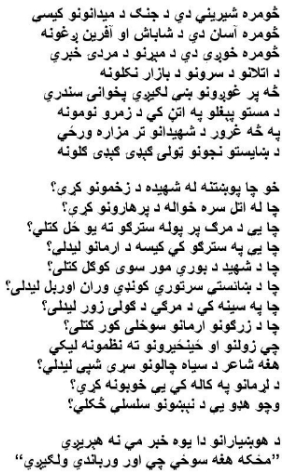

How pleasant are the tales of battlefields?

How easy are the cheers of bravo and praise?

How sweet are the talks of the valour of fearless (men)

And the bazar (market) legends of the heads of heroes?

How soothing the old songs are to the ears

The names of the lion-hearts sung by cheerful dancing (young) girls?

How proudly the flocks of pretty girls like bunches of flower

Go to the shrine of the martyrs?

But, has anyone asked the martyr about his wounds?

Who has talked to the hero about his injuries/cuts?

Has someone looked into his eyes at the crossing of death?

Has someone seen the tale/lore of unmet hopes/unfulfilled desires in his eyes?

Has anyone seen/witnessed the burnt chest of the martyr’s mother?

Has anyone observed the ruined life of the pretty widow?

Has some seen the scorched house/castle of a thousand/countless desires/expectations?

Has the poet, who writes poems to chains and shackles,

Seen the cold dungeon nights?

Has he slept in scorpion dens/pits?

Have his bare bones tasted the ceaseless stings?

I can’t forget this saying of the wise (men),

“The fire burns the land on which it ignites.”